BEHIND THE LENS FEBRUARY 15 2024

by Anna Carnick

A conversation with acclaimed photographer Iwan Baan

ARCHITECTURE PARK JINHUA, CHINA, 2006

Photo © Iwan Baan

Over the past twenty years, Dutch photographer Iwan Baan has circled the globe capturing images that reveal the myriad ways we construct—and respond to—our built environments. Fueled by an intuitive eye and a fascination with the confluence of people and places, Baan’s photographs document architectural achievements, from iconic edifices and megacities to more informal and traditional structures, all while probing how communities around the globe create, in so many different ways, “all kinds of worlds for themselves.”

Baan’s prolific practice has made him one of the most revered photographers of his generation—as evidenced by the current exhibition, Iwan Baan: Moments in Architecture, at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein. The installation is the first major retrospective of Baan's oeuvre and spans an array of architectural subjects with an emphasis on the human experience.

As Baan says, “I’m interested in seeing how an architectural space is really lived with—in the unplanned things, the unexpected human interaction… all these things that an architect doesn’t really have control over... These are the aspects by which we can tell a story of a place.”

Baan spoke to us from his Amsterdam studio.

STEPWELL CHAND BAORI, ABHANERI, RAJASTHAN, INDIA, 2016-2017 BY IWAN BAAN

Photo © Iwan Baan

Anna Carnick/ Congratulations on the exhibition!

Iwan Baan / Thank you. It's been very exciting to work on.

AC/ When did you first know that you wanted to be a photographer? And specifically, when did you realize you wished to focus on architectural environments?

IB/ It was all a bit unplanned really. I've been taking photographs basically my whole life. On my twelfth birthday, I was gifted a camera by my grandmother, and just sort of knew from the get-go what I wanted to do with it. I went on to art school and studied photography, and spent a couple years afterwards doing documentary and commissioned work and so on. In 2004, by coincidence, I met [famed architect] Rem Koolhaas and began working with him. And from one day to another, I was surrounded by architects.

I quickly realized that by working with the field of architecture, I could combine all my own varied interests in places, cities, people, and how structures are inhabited or taken over in very different locations around the world. It was essentially an extension of the kind of photography I’d been doing my whole life—and a concentrated way to feed my own curiosities.

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF QATAR, DOHA, QATAR, 2019; ARCHITECTURE BY ATELIERS JEAN NOUVEL

Photo by Iwan Baan; © Iwan Baan / VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2023

AC/ That makes perfect sense—particularly since one of the things that resonates so powerfully in your work is your emphasis on humankind's relationship to the built environment. Your photos don’t just capture remarkable structures; they depict how people engage with them. Given your experiences and observations over the years, what’s one lesson you’ve learned regarding our connections to the constructed world around us?

IB/Yes, my interest is always in learning how people live around the world. I’ve gathered that many of us [simply take for granted or accept] our own surrounding, built environments as the norm—the houses we live in, for example—but these structures can take vastly different forms in different climates, local circumstances, depending on needs, and so on. Around the globe, people create all kinds of worlds for themselves. I think that’s fascinating.

TIÉBÉLÉ AERIAL VIEW, BURKINA FASO, 2021

Photo © Iwan Baan

MAKOKO, LAGOS, NIGERIA, 2013

Photo © Iwan Baan

AC/ In that spirit, can you tell me about a few specific images in the exhibition that are especially meaningful to you?

IB/ Yes, a few come to mind that demonstrate very different ways to think about the built environment. For instance, there is Lalibela, which are these rock-hewn churches in Ethiopia that are almost 1000 years old. It’s a bit like Petra [in Jordan], which a lot of people know, these churches or temples horizontally carved into the rocks. But in Lalibela, these religious places were carved out vertically into the earth. They are incredible, particularly when you think about the kind of planning and construction required to create the space—by removing material instead of building up material. It’s a completely different concept of space. This structure is in a volatile place that has seen many wars and changes over the centuries, but the space itself has always remained.

BIETE GHIORGIS, ROCK-HEWN CHURCH, LALIBELA, ETHIOPIA, 2012

Photo © Iwan Baan

Then there’s the Kumbh Mela Festival, which is this incredible Hindu festival in India, where they basically build a temporary mega city for what they estimate is between 80 and 100 million people, pilgrims, who visit that place during a span of six to eight weeks. They construct this ephemeral city completely out of bamboo sticks and saris and other fabrics, which then essentially washes away into the Ganges River and comes back 12 years later. It’s another, completely different way of thinking about the permanence of space or ritual space—and how traditions are carried over within a place for hundreds or even thousands of years sometimes.

KUMBH MELA FESTIVAL, PRAYAGRAJ, INDIA, 2013

Photo © Iwan Baan

Versus another place where I was a couple of years ago, the Ise Shrine in Japan. It’s set on two hills within a forest in Mie Prefecture, a couple hours from Osaka. It is one of most important sites in the Shinto religion, and millions of people visit each year [though the public is not allowed in beyond sight of the roofs of the central structures, which are obscured by tall wooden fences].

I've worked with many Japanese architects over the years, and been told many times that I had to visit the Ise Shrine. It’s essentially the golden ratio in Japanese architecture. And the craftsmanship is incredible; it’s made completely of wood, no nails. But every 20 years [in keeping with the Shinto concepts of rebirth and renewal], it’s completely rebuilt. And that’s been happening for millenia.

THE ISE SHRINE IN JAPAN

Photos © Iwan Baan

There are two temples sitting on identical plots beside each other, and after about 12 years they begin building an exact replica of the first one in the plot next to it. It takes about eight years to finish. So every 20 years, you have two identical structures next to each other. I was there at the 20 year mark, which is one of the biggest moments in Japanese culture, where they transfer the spirits from the old shrine to the new shrine and the Shinto priests and the whole royal family are there. And then the entire circle starts again. And I’m very intrigued by these ideas of craftsmanship, tradition, faith, and so on, and also this concept of constant renewal, which you see everywhere in Japan in different ways.

So when you consider all three of these examples, you get a sense of how different cultures are thinking about the permanence of space in such rich and varied ways.

LEFT: MIKIMOTO GINZA 2, TOKYO, JAPAN, 2006; ARCHITECTURE BY TOYO ITO & ASSOCIATES, ARCHITECTS. RIGHT: HOUSE H, TOKYO, JAPAN, 2009, ARCHITECTURE BY SOU FUJIMOTO ARCHITECTS

Photos © Iwan Baan

AC/That's fascinating. I read a quote of yours recently where you said: “What's important is the story, which is very intuitive and fluid. I am not so interested in the timeless architectural image as much as the specific moment in time, the place, and the people there—all the unexpected, unplanned moments in and around the space, how people interact with that space, and the stories that are unfolding there.” It’s a very poetic sentiment. How do you go about achieving that level of resonant storytelling in your work? How do you know when you’ve got that shot?

IB/It's very connected with the kinds of projects I take on, from commissioned projects to more personal interests, such as these three examples, which are driven by my own curiosity into how people create spaces for themselves. But also with commissions from architects; I’m not only photographing the building. There should be another story around it to make it interesting—a story about how it’s used, what people do there, where it’s built, how it’s built, how it fits into an environment or how it completely juxtaposes with its surroundings. Beyond an architect’s elaborate plans and ideas of how a place should work, I’m always interested in the reality, and when there’s an outer friction around it—whether that’s the newness of a place, the traditions connected to it, how people take it over, how things work, or how they sometimes don’t work. I’m much more interested in that moment when the architect leaves the project, and people take it over. I like to see what happens in those moments.

LEFT: NATIONAL STADIUM, BEIJING, CHINA, 2008; ARCHITECTURE BY HERZOG & DE MEURON. RIGHT: CONSTRUCTION OF THE NATIONAL STADIUM, BEIJING, 2007

Photos © Iwan Baan

"I’m much more interested in that moment when the architect leaves the project, and people take it over. I like to see what happens in those moments."

-Iwan Baan

AC/ Your work strikes me as quite anthropological in that way. And whether it's a large-scale, star architect project or vernacular architecture, when you photograph these settings as they’re being engaged—when you highlight real human interaction—it also creates a point of access for the viewer.

IB/ Yeah. And I think traditional architectural photography—and please don’t call me an architectural photographer, I hate that term! [laughing]—is a kind of service, where you’re showing the best image of a building, often captured at sunset. But I think that really great architecture can look strong in any condition. I’m interested in seeing how an architectural space is really lived with—in the unplanned things, the unexpected human interaction, or even the garbage on the street, all these things that an architect doesn’t really have control over, these things together can tell a great story about what makes a particular place special and unique. These are the aspects by which we can tell a story of a place.

LEFT: TESHIMA ART MUSEUM, TONOSHO, JAPAN, 2010; ARCHITECTURE BY RYUE NISHIZAWA. RIGHT: NATIONAL TAICHUNG THEATRE, TAIWAN, 2016; ARCHITECTURE BY TOYO ITO & ASSOCIATES, ARCHITECTS.

Photos © Iwan Baan

AC/ So how would you describe your role and relationship to the architects with whom you work?

IB/Funnily enough, I started working with Rem Koolhaas in that vein. He was also not so interested in capturing just a pristine image. He also wanted to say something more, and that’s where we connected. And that's how I approach all these architectural projects. It's a constant zooming in and out from very personal moments with people, where the architecture almost disappears in a sense, to this larger aerial perspective, where the building becomes just this little element in an image that relates how it fits, or not, into the carpet of the surrounding city or environment.

And yet, I think with all these approaches, it’s always very intuitive. And it’s always driven by curiosity. I try to go to a place without too much prior knowledge, and to enjoy discovering what makes each place unique. I try to remain very open.

AC/ That's lovely. I’m actually reminded of a photograph you took years ago during Hurricane Sandy. I was living in New York at the time, and recall the image so clearly. You took a photograph of the city from an aerial view, and captured this iconic metropolis in such an unexpected moment—when the city had become, as you put it back then, like two cities. Part of the city had lost power and was just blanketed in ominous darkness; the rest remained this illuminated, seemingly vibrant world at night. I really respect how you reacted to this difficult moment, capturing this familiar place with open eyes, and identifying such a powerful visual frame to help tell the story. Can you share a bit about how you got that shot?

NEW YORK AFTER HURRICANE SANDY, USA, 2012

Photo © Iwan Baan

IB/Of course. You can't plan for an extreme event like this, of course, but it was almost second nature for me, wanting to go up in the air to better understand how the storm had affected the broader landscape. I’d arrived in the city the day before, and subways and streets were flooded and electricity was cut. I was stuck in my hotel room, like so many, and I was trying to figure out how to take photos without any light. The aerial perspective just made sense to me, to show which parts did and didn’t have electricity.

And then an awful lot of coincidences perfectly aligned and I was able to find someone to fly me there in a helicopter—and I happened to have just received a new Canon camera with the latest technology which was incredibly sensitive, and actually made it possible to capture that shot from a moving helicopter at night in complete darkness. So all these things serendipitously fit together, so I could then pay attention to the image. And it often sounds a lot like that. You can’t really plan for these pictures, and you just have to be completely open and work with all the tools you have at hand. And then life always plays out in front of us.

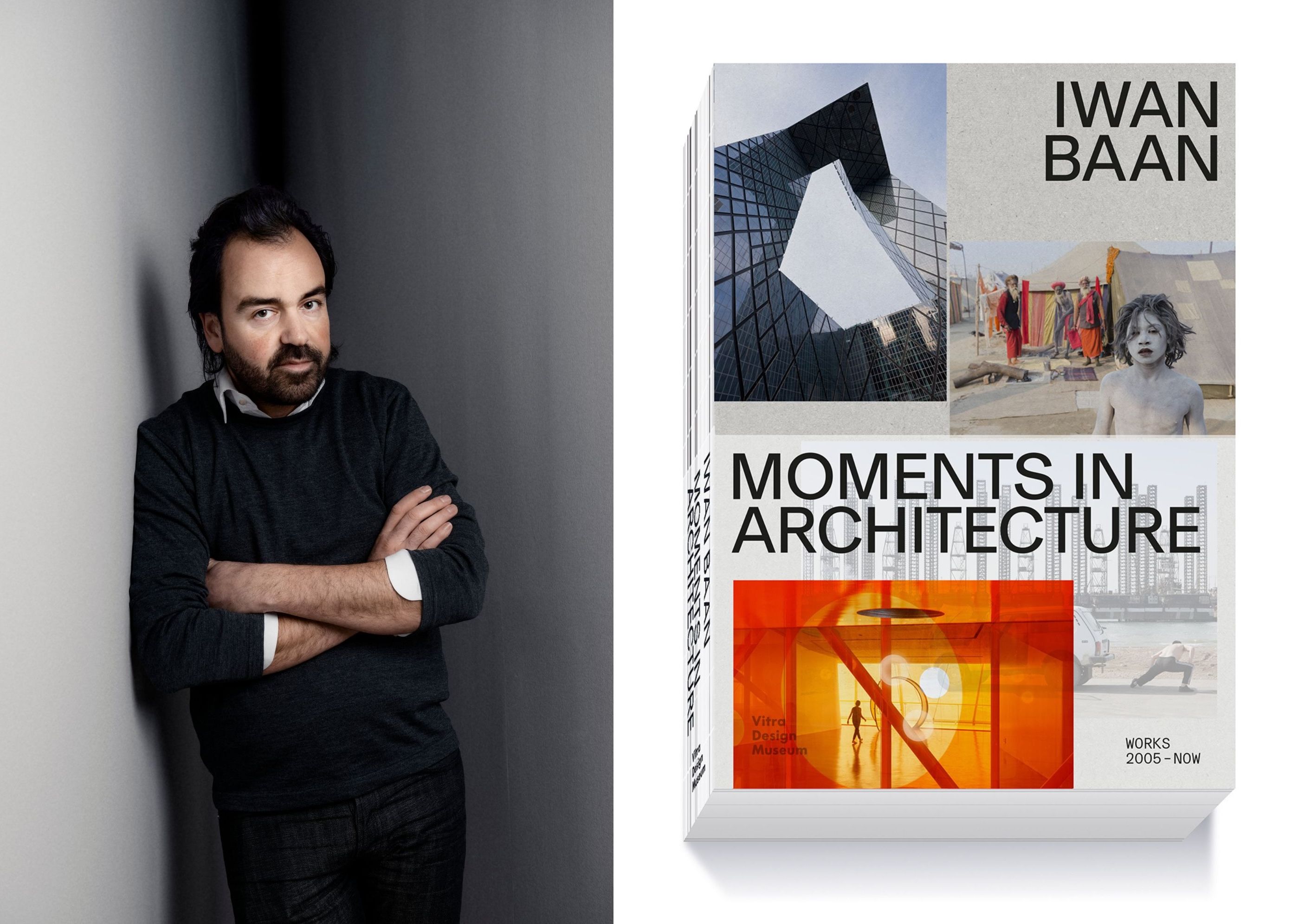

FROM LEFT: PHOTOGRAPHER IWAN BAAN AND THE COVER OF THE CATALOG FOR BAAN'S CURRENT SHOW: IWAN BAAN: MOMENTS IN ARCHITECTURE AT VITRA DESIGN MUSEUM

Portrait photo by Jonas Eriksson; All book cover images by Iwan Baan; Design by Haller Brun

AC/ Are there any other particular moments that stand out to you as particularly striking or perhaps gratifying experiences?

IB/ I suppose the latest things are always top of mind. But in general, for me, it’s all these different moments in time where things suddenly become complex and a lot of different worlds clash together, scrape together. These create such interesting scenes.

At the moment, I am finishing a book on two cities, Las Vegas and Rome—seemingly counter opposites, 2000 years apart, but in some ways, also very similar. The project raises questions about authenticity and artificiality, asking: What makes a place real? What are people searching for? The book comes out this spring with Lars Müller Publishers.

ROME, PHOTOS BY IWAN BAAN

Photos © Iwan Baan

LAS VEGAS, PHOTOS BY IWAN BAAN

Photos © Iwan Baan

AC/I’m excited to see it. And then there’s the exhibition of course.

IB/ Yes, there’s just a few weeks left to visit the exhibition at the Vitra Design Museum, and then it will travel for the next few years, including to ICO Museum in Madrid this summer.

AC/What do you most hope people take away from seeing the exhibition?

IB/Many people are familiar with my architectural commissions, but it was really exciting to bring together all these different aspects of my work to help people understand what I’m really doing and trying to show through my photographs—and how I’m using essentially the same approach within vastly different places and circumstances.

EXTERIOR AND INSTALLATION VIEWS OF THE VITRA DESIGN MUSEUM EXHIBITION, IWAN BAAN: MOMENTS IN ARCHITECTURE

Photos by Mark Niedermann; © Vitra Design Museum

We actually brought the museum back to its original state, as Frank Gehry had designed it [following various shifts over the years]—and so we opened up all the skylights and all the connecting spaces again—which was particularly gratifying as I feel like all my work is about space, so it felt good to present it in a space as the architect had originally intended.

The result is that there are four main rooms, from which you can always see into the other spaces. We highlighted four aspects of my work—from my early explorations in China, and then more of my commissioned work with architects, and then cities, and finally images of informal and/or traditional vernacular spaces. So you’re suddenly seeing the connections between the spaces and the work. And it’s been exciting to work with the Museum. It’s been a great opportunity to show and tell.

AC/ Thank you so much, Iwan!

Iwan Baan: Moments in Architecture is on view until March 3rd at Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein. Baan’s upcoming book, Rome - Las Vegas, will be published later this year by Lars Müller Publishers. Learn more about Baan here.

The conversation above has been edited for clarity and flow.