IN THE MIX SEPTEMBER 3 2021

by Design Miami

An excerpt from the landmark new publication, Designing Motherhood; Foreword by Alexandra Lange

JEAN-PAUL GOUDE/ CONSTRUCTIVIST MATERNITY DRESS; NEW YORK, 1979. CREATED IN COLLABORATION WITH ANTONIO LOPEZ. DESIGNED WHEN GRACE JONES WAS PREGNANT WITH HER AND GOUDE'S SON, PAULO

Photo © Jean-Paul Goude

This month, Designing Motherhood, a landmark, multipart project exploring the world of human reproduction through the lens of design, launches its latest iterations: a book published by MIT Press and an exhibition at Philadelphia’s Center for Architecture and Design. With empathy and savvy, the project—which also includes public programming, design curriculum, and a popular Instagram feed—explores the human experience of designs that are connected to pregnancy, birth, postpartum, and more. It is a fresh and important look at, as design critic Alexandra Lange writes in her wonderful foreword to the book, “a field hiding in plain sight, obscured by its own ubiquity and sidelined by everyday sexism.”

On the eve of its publication, we’re thrilled to present Lange’s foreword below.

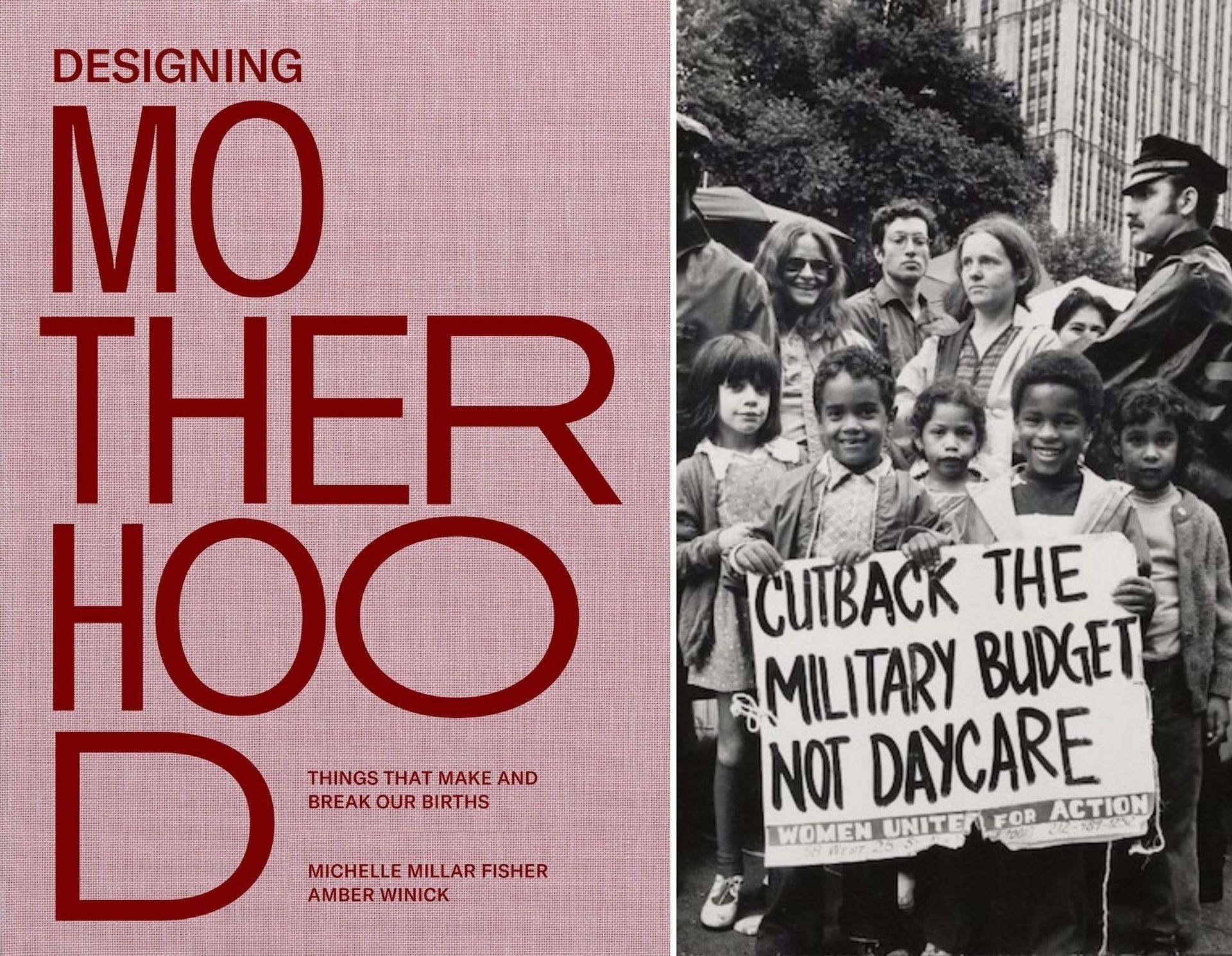

DESIGNING MOTHERHOOD, PUBLISHED BY MIT PRESS | CHILDREN DEMONSTRATING FOR AFFORDABLE CHILD CARE IN NEW YORK CITY

Photo by Bettye Lane, August 20, 1974. From Designing Motherhood; courtesy of Schlesinger Library

“There is nobody against this—NOBODY, NOBODY, NOBODY but a bunch of . . . a bunch of MOTHERS!” Waiting for his turn to speak at a hearing about the city’s plans to run a divided roadway through Washington Square Park in New York, parks commissioner Robert Moses had heard enough. Although Jane Jacobs and Shirley Hayes, the chief organizers of the Greenwich Village group that had arranged photogenic picket lines of children opposing the loss of their play space, had yet to have their say, Moses was incredulous that they might prevail. Despite his close study of the levers of power, he had failed to consider how those traditionally considered the weakest—women and children—might win a public relations battle. They did so by transforming a subject, motherhood, that women were by their nature supposed to know best from a private concern to a public one, moving it from the home to the streets.

Their protest described an arc that is repeated again and again in the design objects whose stories are told in Designing Motherhood. This arc connects the personal to the political, the interior to the city, and transforms us versus them to, in the end, simply us—because we all arrive here via some process of birth and, at some point and in some way, we all mother. The designs in this book go beyond binaries and biology.

Maternity clothes and baby carriers, because of their temporary use and identification with the domestic sphere, have received little attention in histories of design, a reality I found in my own research on toys. I was among the first followers of the Designing Motherhood Instagram account, which for the last two years has served as a teaser and research lead for this project. In multiple ways, I have already learned as much from the account as from many scholarly books. This approach of research-in-public, a terrific symbol of the energy and fresh ideas the organizers bring to bear on the subject, is significant. Design history today must go beyond the physical walls of the museum or the printed page to consider, as this project does, the social, scientific, and political implications of objects.

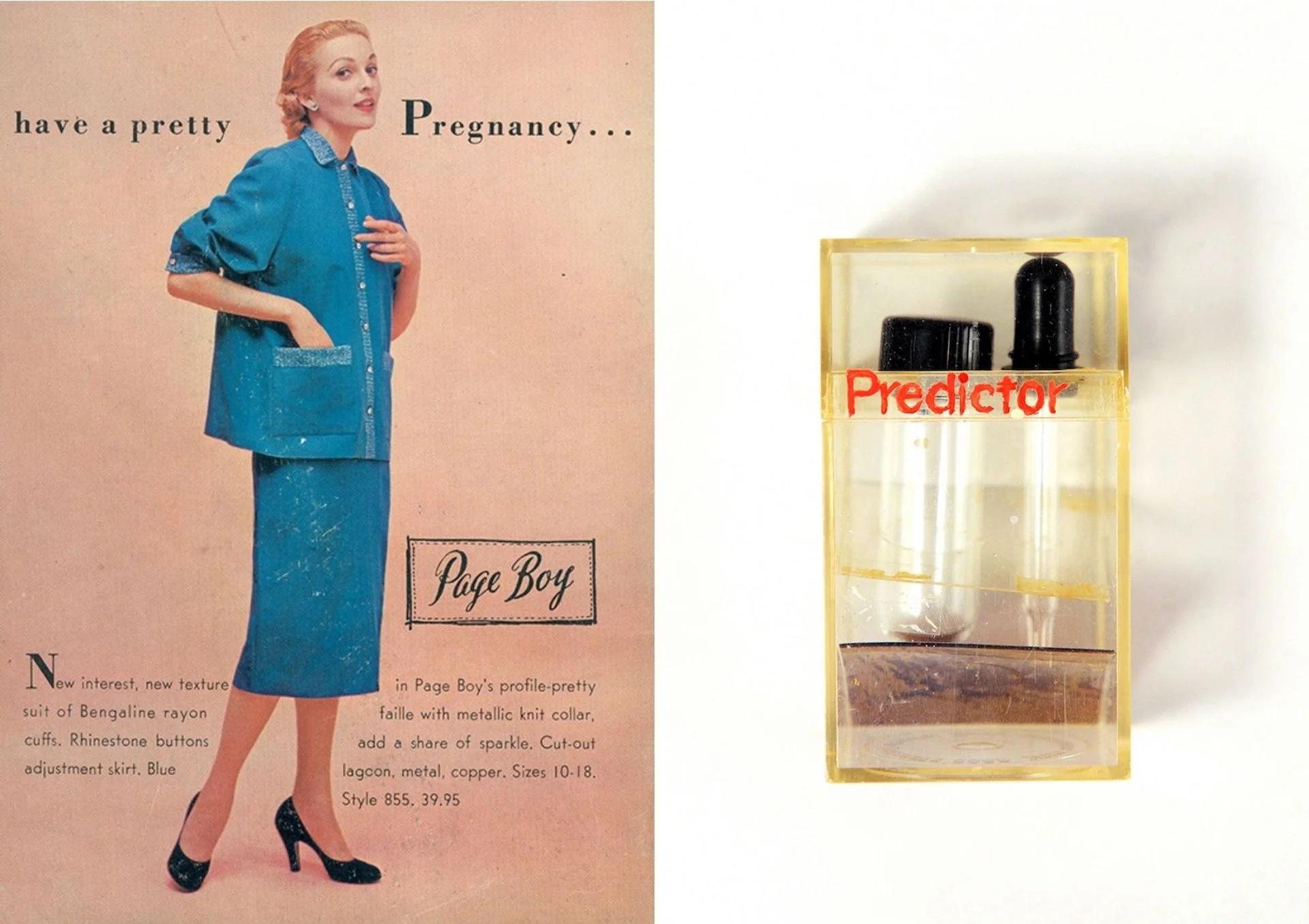

TIE-WAIST SKIRT FEATURED ON THE BACK COVER OF THE PAGE BOY FALL/WINTER CATALOGUE 1952 | PREDICTOR HOME PREGNANCY TEST KIT, 1971, DESIGNED BY MEG CRANE

Left: Photo courtesy of the Texas Fashion Collection, University of North Texas Libraries | Right: Photo courtesy Brendan McCabe

Here, euphemisms like “in an interesting condition” and “up the duff” and the French “enceinte” are replaced with focused looks at online fertility trackers, gender-reveal parties, and day-by-day social media updates. Written and edited by Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick, but embracing a plurality of voices and experiences in the form of interviews, contributor essays, and visual materials, Designing Motherhood underlines just how many design fields contribute to the lifelong project of motherhood. Books, fashion, and industrial, automotive, and medical designs each have a role to play from preconception (and contraception) to death, from the ritualistic taking of prenatal vitamins to the poignant memorials of pregnancy-loss tattoos.

The reason for the scatteration of fields responsible for the products of motherhood becomes clear through the examples collected in this volume. Motherhood was a field hiding in plain sight, obscured by its own ubiquity and sidelined by everyday sexism. The famous innovators of motherhood were more often medical men than people who parented, including Dr. Benjamin Spock, whose 1946 Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care defined the post–World War II middle-class childrearing experience, and the earlier and more sinister Dr. J. Marion Sims, considered the father of modern gynecology, who only achieved that renown by testing his unproven surgical methods on enslaved Black women. In Designing Motherhood they are given equal billing with Elsie Frankfurt, the mother of modern maternity wear, who created the tie-waist skirt so that her pregnant sister would not look like a “beach ball in an unmade bed.”

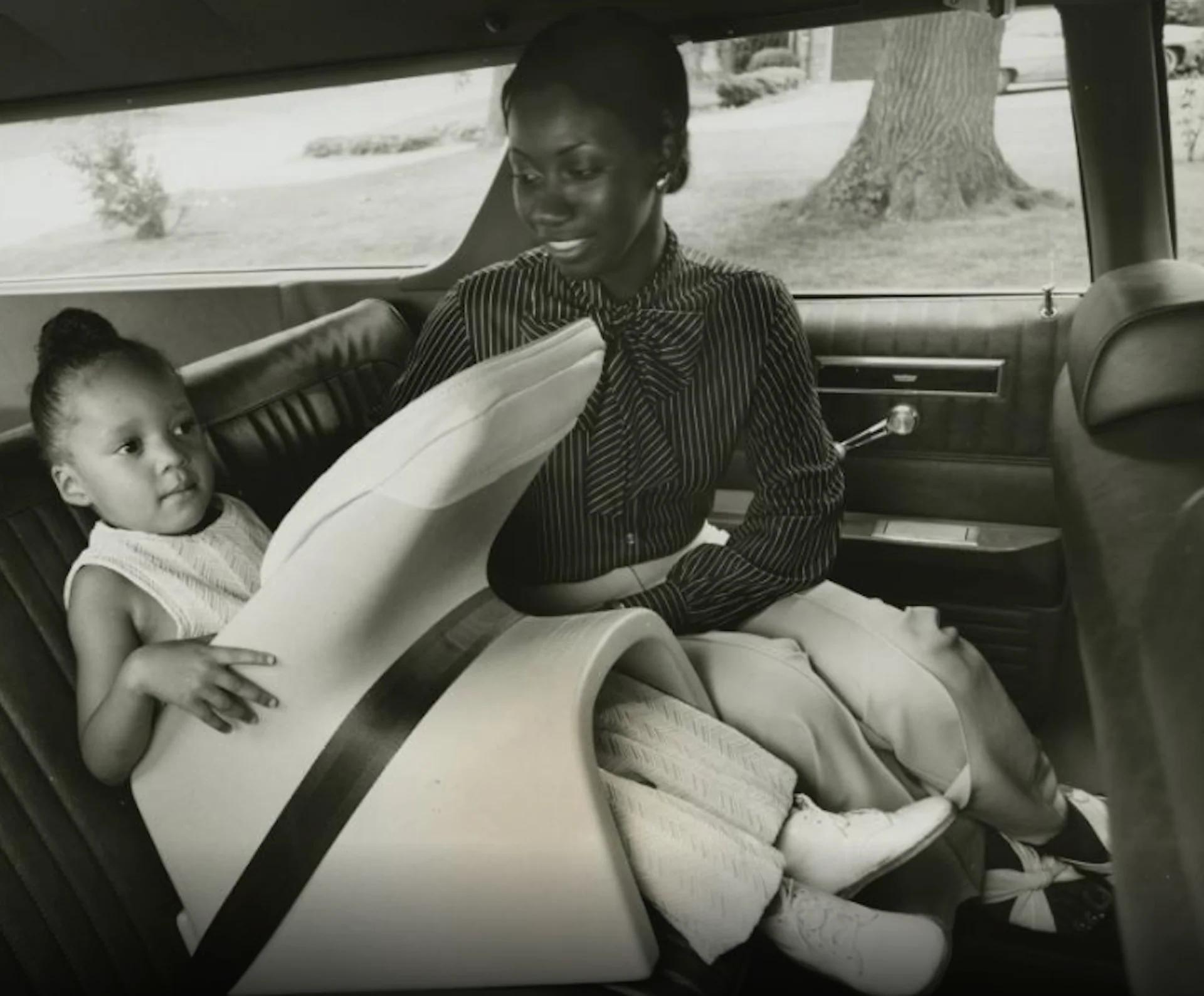

FORD MOTOR COMPANY'S TOT-GUARD, 1973

Photo courtesy of the Collections of The Henry Ford Museum

I wrote this foreword during at-home quarantine in Brooklyn in June 2020, witnessing the simultaneous pandemics of Covid-19 and structural racism collide. Zoom meetings and video calls have put family life on display at work as never before: the desktop picture of the kids is now a live show. But while both parents may be at home, the burden of homeschooling has disproportionately fallen on mothers, according to a New York Times poll, setting up potentially disastrous long-term consequences for their careers. And for some, even a successful career is no protection. As Dr. Khiara Bridges points out in the interview titled “#ListenToBlackWomen,” Black college-educated, economically stable women in the United States are still three to four times more likely to die during or immediately after childbirth than White women with less than a high school education and rockier financial foundations. The authors demonstrate the many ways our struggles as women, people of color, and non-gender-conforming persons are designed into society, and how we can—how we must—design our way out. They have been guided throughout the project by thought partners and longtime grassroots advocates at Philadelphia’s Maternity Care Coalition.

“FOUR GENERATIONS” FROM THE SERIES MOTHER: A COLLECTIVE PORTRAIT, 1997

Photo by and courtesy of Mary Motley Kalergis

The focus on the design of systems is woven throughout the book and the wider project. It animates graduate student Alexis Hope’s first-person account of the “Make the Breast Pump Not Suck” hackathon at MIT, organized by Hope and a fellow graduate student (now professor), Catherine D’Ignazio. After the hackathon, both women realized that it wasn’t so much the device that sucked (though it does), but the circumstances pushing women toward a return to work long before the pediatrician-recommended six months of breastfeeding (also controversial and covered in the essay on formula). Hope writes, “Framing breastfeeding as an individual choice, without reflect- ing on the circumstances that guide people’s ability to make a choice (for example, going back to work may be the only economically feasible choice; many don’t have the time or a place to pump at work; and so on), is misguided.” What she and D’Ignaizio ultimately decided to hack was not the breast pump but America’s lack of a federal family leave policy.

MAMA BREASTFEEDING, FEATURED IN THE NEW BOOK DESIGNING MOTHERHOOD

Photo by Dr. Gayle Neslon; courtesy of Gabriella Nelson

There is also room for joy in Designing Motherhood, perhaps best expressed by Fisher’s essay on “model, signer, actor, provocateur” Grace Jones’s 1979 performance wardrobe of a “maternity mega-dress,” designed by Antonio Lopez and expectant father Jean-Paul Goude. Outfitted in the mega-dress, with its bright colors, empire waist, ceinture of spiky cardboard triangles, and tricorne hat with an exclamation point, Jones’s image was a far cry from the porcelain Mother and Child figurines of the past, or even the girdled conformity of the postwar era, when a mother’s clothes often matched her brand new kitchen. Jones capped her successful album launch with a disco baby shower, complete with runway. “Show us the stomach, honey!” someone in the crowd chanted, and Jones showed them why no one should underestimate the power of a bunch of mothers. ◆

This text is excerpted from Designing Motherhood: Things that Make and Break Our Births by Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick. Reprinted with Permission from The MIT PRESS. © 2021.

Read our new interview with the creative team behind Designing Motherhood here.

To learn more about Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births, visit designingmotherhood.org. The latest exhibition at the Center for Architecture and Design in Philadelphia runs September 10-November 14th; the exhibition at the nearby Mütter Museum runs through May 2022.