BEHIND THE LENS FEBRUARY 6 2024

by Wava Carpenter

Photographer Timothy Doyon on the art of documenting art

TIMOTHY DOYON/ DR. SOAPER BY RICHARD PATTERSON FOR TIMOTHY TAYLOR

Photo © Timothy Doyon

The torrent of photographic images we encounter everyday in our increasingly digital lives has had a twofold effect. On the one hand, seeing far-flung people, places, and things in photographs makes them seem closer, more familiar, allowing us to feel more connected to a wider slice of the world.

On the other hand, the ubiquity of images has heighted our awareness that photography is, after all, a creative medium—by definition a mediated view of reality, one that the creator constructs through myriad technical and aesthetic choices. As Ansel Adams famously said, “You don’t take a photograph, you make it.”

TIMOTHY DOYON/ MARTIN KIPPENBERGER: PAINTINGS 1984-1996 AT SKARSTEDT GALLERY

Photo © Timothy Doyon

Photographing fine art, then, brings a unique challenge. Artists and institutions demand their artworks be documented in archival-quality photography that faithfully preserves the artists’ intentions. Photographers specialized in this kind of work are tasked with using their subjective medium to create objective-seeming representations, replicating as directly as possible each artworks’ distinct colors, textures, and in-person experience.

Anyone who has tried to memorialize a museum tour with a phone camera knows this is no easy task. Capturing artworks as they are meant to be seen is an art in its own right.

For our latest Behind the Lens column, we’re spotlighting Brooklyn-based photographer Timothy Doyon, a master of fine art documentation as well as installation and interiors shoots.

TIMOTHY DOYON/ SELF PORTRAIT

Photo © Timothy Doyon

Doyon’s sharp eye and technical expertise has attracted an impressive roster of clients, from galleries and artists to interior designers—Hauser & Wirth, Friedman Benda, Ortuzar Projects, Judd Foundation, David Zwirner, and Charlap Hyman & Herrero, to name a few. Read on to discover the experiences and approaches that feed his practice—and to enjoy some stellar art and interiors photography.

TIMOTHY DOYON/ THE NEW YORK HOME OF COLLECTOR AND GALLERIST BARRY FRIEDMAN

Photo © Timothy Doyon

Wava Carpenter/Where did you grow up, and what aspects of your upbringing sparked your interest in photography?

Timothy Doyon/ I was born and raised in Bennington, an artsy town in Vermont. There I took full advantage of my high school’s art classes, one of which was photography. I immediately fell in love with the medium.

I found it fun to discover new places and capture everyday things in a different way from how everyone else sees them. At the same time, because I was living in a small town, I found it eye-opening to look at photographs from across the world. Sharing and viewing images is an inspiring way to experience new things and show others new ways of looking.

TIMOTHY DOYON/ FAUSTO MELOTTI: THE DESERTED CITY AT HAUSER & WIRTH

Photo © Timothy Doyon

WC/When did you move to Brooklyn, and how does the city feed your practice?

TD/After graduating college in 2009, I had a near-death experience, which served as a wake-up call. The following year, I swallowed my fears and moved to New York without a job, because I wanted to experience the city and accomplish my personal goals before it was too late. I saw New York City as a mecca photography-wise.

Living in the city, I am surrounded by great artists, galleries, museums, architects, and interior designers. There is high demand here for documentation, but it can also be quite mercenary at times. With my attention to detail, commitment to quality work, and good relationships, I have gotten great repeat clients, which keeps me determined. It works for me.

TIMOTHY DOYON/ HANNAH LEVY: BONE-IN AT JEFFREY STARK

Photo © Timothy Doyon

WC/How did your focus on art documentation, installations, and interiors develop?

TD/Looking back, I would argue that art documentation developed during my freshman year in college—beginning with my friendships with upperclassmen. Having older friends granted me a unique opportunity to photograph their work. Everyone needed to document their senior exhibits, but the photo majors graduating with them were always busy producing their own projects. Being younger and having a different class schedule gave me “clients” and interesting subject matter to photograph in the studio. I learned photography and lighting by narrowing down to the exact concentration I am still doing today.

My life-long interest in art and design led me to minor in art history and visual communication. Touring the city with private viewings of work by some of the greatest artists—both alive and dead, modern and contemporary—is a dream job. I went from seeing artworks in textbooks to photographing them, often in very intimate settings. I am now responsible for visually recording artwork for artists, galleries, and enthusiasts.

TIMOTHY DOYON/ PAINTINGS BY DIANA AL-HADID FOR KASMIN GALLERY AND FRANK BOWLING FOR GRAHAM STEELE

Photos © Timothy Doyon

WC/How would you describe your approach to capturing artworks and installations, particularly when the goal is to create a seemingly unmediated representation—to capture artwork as close as possible to the artist’s intention?

TD/Great question. Focusing on the artwork’s materials, my first objective is to light individual works to make them appear true to life. Lighting is very subjective, and my lighting may appear differently than it would in an artist’s studio or the spotlights of a gallery.

I think it’s my job to take into consideration colors, background, reflections, highlights, and shadows and then light the piece as it would appear in soft, neutral, even light. I’ll use strobe lights and color correcting methods to achieve this look, but everything is case-by-case due to the wide range of artworks that exists.

I strive to make individual works appear as they would on a bright cloudy day without distracting shadows. It is unfair and inaccurate to take liberties to artistically light the artwork for documentation purposes. This is why I document as accurately as possible for true archival quality.

Installation photography is different. I keep the gallery lighting unless instructed differently by my client. It’s important to have the audience’s view replicate the experience of attending in person. I’ll photograph around the space as if someone were walking through an exhibition.

Generally, I tend to photograph installations more straight-on than most art documentation photographers, because I find that foreshortening perspectives are distracting and can cause lens distortion.

TIMOTHY DOYON/ DARK SECRETS BY WENDELL CASTLE FOR FRIEDMAN BENDA

Photo © Timothy Doyon

WC/How does your approach change when capturing two-dimensional versus three-dimensional works?

TD/The major difference between photographing two-dimensional and three-dimensional art is camera placement. Unlike a flat painting, you can choose where to place your camera for a sculpture. Do you keep the camera at eye level? Do you shoot it low to make it look large? Perhaps you photograph it midway through. This is a very subjective call.

In some cases, artists will specify how they want their work to look; other times I have to decide. With years of experience and understanding what makes the art unique, I let the work dictate what looks best. Remember you can also move the artwork in addition to moving the camera for an infinite amount of content.

TIMOTHY DOYON/ PRIVATE RESIDENCE IN NEW YORK DESIGNED BY CHARLAP HYMAN & HERRERO

Photo © Timothy Doyon

WC/How would you describe your approach to capturing interiors?

TD/I love to work with natural light whenever possible. Upon entering an interior, I like to do a walkthrough with the client. During this time, I'll familiarize myself with the number of spaces in need of documentation while also observing how the sunlight affects them. I’ll often use my phone and “work” the room for the best angles.

One by one, I’ll frame up the shots that look best, showing those images to the client on a large screen in real-time. I like collaborating with my clients rather than simply providing a service. It's very important that the photographs also reflect the interior designers’ skills and aesthetic choices in accordance with a photographic standard.

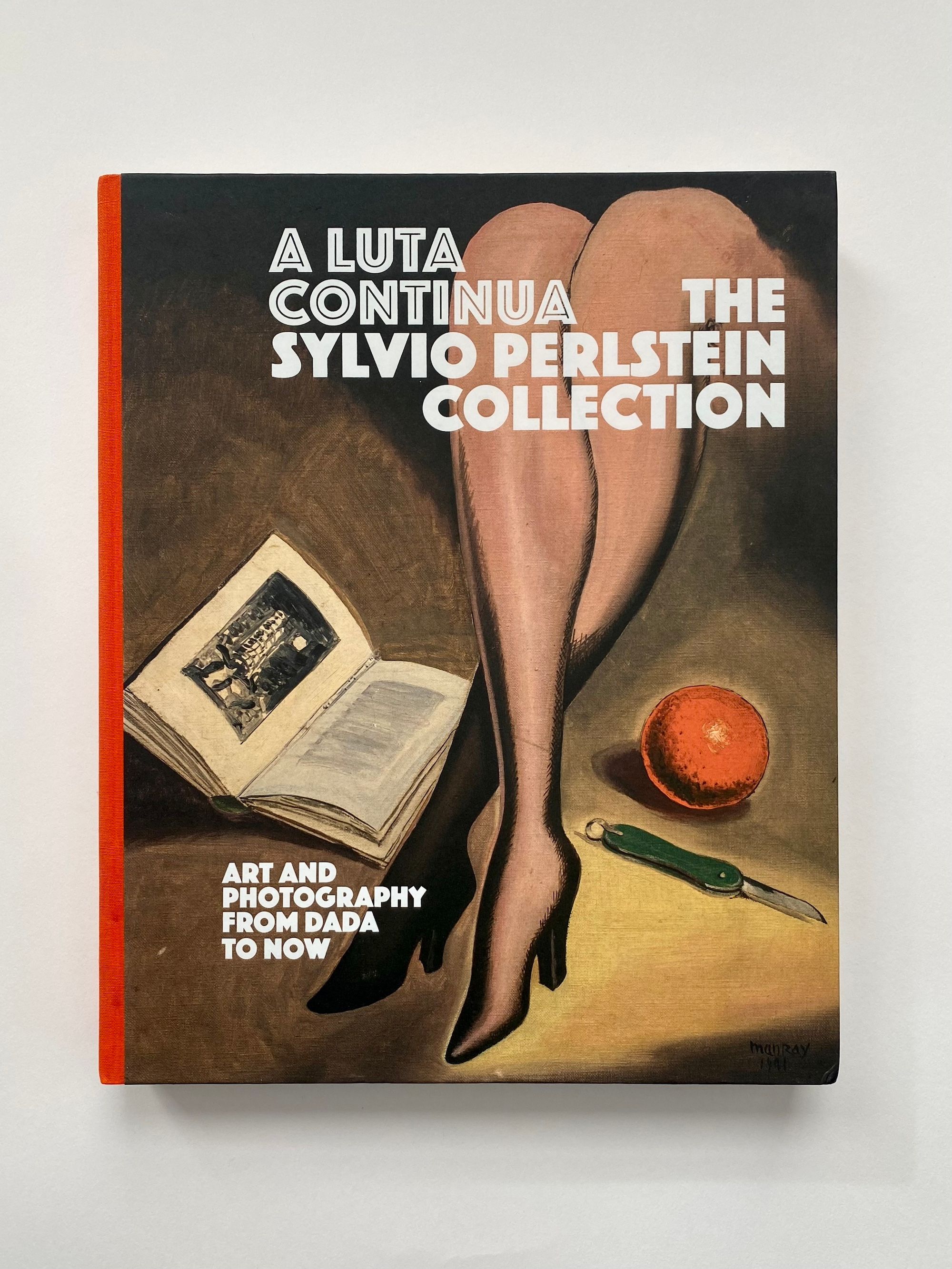

A LUTA CONTINUA: THE SYLVIO PERLSTEIN COLLECTION: ART AND PHOTOGRAPHY FROM DADA TO NOW, A BOOK PROJECT THAT TIMOTHY DOYON PHOTOGRAPHED FOR HAUSER & WIRTH

Photos © Timothy Doyon

WC/Can you share some experiences you’ve had as a photographer that have been particularly meaningful—some moments that have stayed with you and influenced your path going forward?

TD/There are countless experiences that I consider meaningful and that helped me stay on course. Many meaningful experiences were my firsts—the first blue-chip gallery, first museum job, first magazine spreads, etc.

One of those that stayed with me was a collection book I photographed with Hauser & Wirth, capturing over 200 images with a fast turn around. The work was challenging—tons of neon lights, massive floor-to-ceiling works, tons of reflections. Overcoming those challenges and holding my composure to ensure a quality final product gives me pause for appreciation. Sometimes holding that huge hardcover filled with my photographs, I think, “Wow, anything could be next, and I could tackle it.”

TIMOTHY DOYON/ SELF PORTRAIT

Photo © Timothy Doyon

WC/ Is there a dream project you have in mind for the near or long term?

TD/My next project is a series of artist’s studios and dwellings. Combining my two photographic concentrations, I want to introduce the audience to a “behind the scenes” look at how artists live and operate—something I often am lucky to be privy to.

I love seeing how other people really live. It’s a great way to learn about someone, and I want to showcase not only their artwork, but also their personalities and style as well as the tchotchkes that they own to make them happy in their sacred spaces.

You can find more of Timothy Doyon’s work at timothydoyon.com and follow him on Instagram @timothydoyon